| |

Lent (the word "Lent" comes from the Old English "lencten," meaning "springtime) lasts from Ash Wednesday to the Vespers of Holy Saturday -- forty days, never minding the six Sundays which don't count as "Lent" liturgically. The Latin name for Lent, Quadragesima, means forty and refers to the forty days Christ spent in the desert which is the origin of the Season.The last two weeks of Lent are known as "Passiontide," made up of Passion Week (which begins on Passion Sunday) and Holy Week (which begins on Palm Sunday). The last three days of Holy Week -- Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday -- are known as the "Sacred Triduum." Here for your use is a pdf file of the scheme of the Lenten season.

The focus of this Season is the Cross and penance, penance, penance as we imitate Christ's forty days of fasting, like Moses and Elias before Him, and await the triumph of Easter. We fast (see below), abstain, mortify the flesh, give alms, and think more of charitable works. Awakening each morning with the thought, "How might I make amends for my sins? How can I serve God in a reparative way? How can I serve others today?" is the attitude to have.

As we meditate on "The Four Last Things" -- Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell -- we also practice mortifications by "giving up something" that would be a sacrifice to do without. The sacrifice could be anything from desserts to television to the marital embrace, and it can entail, too, taking on something unpleasant that we'd normally avoid, for example, going out of one's way to do another's chores, performing "random acts of kindness," getting out of bed immediately after waking and not dallying under the blankets in the morning, taking cold showers instead of hot ones, etc. A practice that might help some, especially small children, to think sacrificially is to make use of "Sacrifice Beads" in the same way that St. Thérèse of Lisieux did as a child. Note, though, that Sundays -- even the Sundays of Lent -- are not penitential days; they are always celebratory days of rejoicing. So if you've given up sweets for Lent, you can indulge some on Sundays, even during this penitential season (this is why Sundays aren't counted at all as the days "of Lent." If you go by the calendar, Lent seems to last for 46 days -- if you count the Sundays. But Catholics don't include those Sundays, so Lent consists of 40 days).

Ideally, the practices one gives up and takes on during Lent should center around eliminating a particular vice, or bad habit, one has, and focus on cultivating the vice's opposite virtue, or good habit. You can learn more about vice and virtue, generally, on the Catholic Moral Thinking page; after reading, try to discern which vice you most need to eliminate from your life, and which virtue you need to develop (here, the Becoming Virtuous pages may be of service to you). Let your Lenten sacrices be those that best help you eradicate your most problematic vice by helping you develop the virtue that defeats it. Provided here is a Lenten Checklist in pdf format to help you organize your thoughts and Lenten routine: Lenten Checklist.

Don't try to do too much! Do what you're able to do without becoming frustrated or overwhelmed. Carry out your sacrifices without complaint and without making others miserable. And don't make a contest out of your sacrifices; in fact, it's best to keep them to yourself. Another thing to not do is to pretend as if giving up your favorite sin is a proper Lenten sacrifice: sin is something you shouldn't be doing anyway! Yes, most definitely give up that sin -- but also add the sacrifice of something good, something allowable, something that is perfectly licit to enjoy in an ordinate way. And as you go along, know that offering up your sufferings for the good of someone you love can help keep you motivated.

Because of the focus on penance and reparation, it is traditional to make sure we go to Confession at least once during this Season to fulfill the precept of the Church that we go to Confession at least once a year; this prepares us to follow the precept of receiving the Eucharist at least once a year during Eastertide. A beautiful old custom associated with Lenten Confession is to, before going to see the priest, bow before each member of your household and to any you've sinned against, and say, "In the Name of Christ, forgive me if I've offended you." One responds with "God will forgive you." Done with an extensive examination of conscience and a sincere heart, this practice can be quite healing (also note that confessing sins to a priest is a Sacrament which remits mortal and venial sins; confessing sins to those you've offended is a sacramental which, like all sacramentals one piously takes advantage of, remits venial sins. Both are quite good for the soul!)

Lent is a particularly good time to otherwise make amends and rebuild broken relationships. Pray for the ability to truly forgive the repentant who've wronged you, and consider those whom you've wronged and whose forgiveness you should seek. Examine your entire life, year by year, looking for ways you've failed, lied, broken God's laws, harmed others, etc. Ask for a contrite and humble heart, and for the fortitude to make right what you've done wrong.

In addition to mortification and charity, seeing and living Lent as a forty day spiritual retreat is a good thing to do. Spiritual reading should be engaged in, over and above one's regular Lectio Divina. Maria von Trapp recommended "the Book of Jeremias and the works of Saints, such as The Ascent of Mount Carmel, by St. John of the Cross; The Introduction to a Devout Life, by St. Francis de Sales; The Story of a Soul, by St. Thérèse of Lisieux; The Spiritual Castle, by St. Teresa of Avila; the Soul of the Apostolate, by Abbot Chautard; the books of Abbot Marmion, and similar works." You can find all of these books, and many more, in this site's Catholic Library, and I provide them here, along with a few other selections:

As to prayer, praying the beautiful Seven Penitential Psalms (Psalms 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, and 142) is a traditional practice. It is most traditional to pray all of these each day of Lent, but if time is an issue, you can pray them all on just the Fridays of Lent, or, because there are seven of them, and seven Fridays in Lent, you might want to consider praying one on each Friday. These Psalms, which include the Psalms "Miserére" and "De Profundis," are perfect expressions of contrition and prayers for mercy. So apt are these Psalms at expressing contrition that, as he lay dying in A.D. 430, St. Augustine asked that a monk write them in large letters near his bed so he could easily read them.

Another great prayer for this season is that of St. Ephraem, Doctor of the Church (d. 373). This prayer is often prayed with a prostration after each stanza:

O Lord and Master of my life, take from me the spirit of sloth, despondency, lust of power, and idle talk;

But grant rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love to thy servant.

Yea, O Lord and King, grant me to see my own transgressions, and not to judge my brother; for blessed art Thou unto the ages of ages.

In the East, this prayer is prayed liturgically during Lent and is followed by "O God, cleanse me a sinner" prayed twelve times, with a bow following each, and one last prostration.

Another prayer to be mindful of is the En ego, O bone et dulcissime Iesu (Prayer Before a Crucifix. On all Fridays during Lent, one may gain a plenary indulgence, under the usual conditions, by reciting this prayer before an image of Christ crucified.

Other devotions to focus on particulary during Lent include praying the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary and making the Stations of the Cross (on Fridays especially).

Of special note, too, is that every single day of this season has an associated station church.

Food in Lent

According to the 1983 Code of Canon Law, the rule for the universal Church during Lent is to abstain on all Fridays and to both fast and abstain on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

Some traditional Catholics might voluntarily follow the older pattern of fasting and abstinence during this time, which for the universal Church required:

- Ash Wednesday, all Fridays, and all Saturdays: fasting and total abstinence. This means 3 meatless meals -- with the two smaller meals not equalling in size the main meal of the day -- and no snacking.

- Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays (except Ash Wednesday), and Thursdays: fasting and partial abstinence from meat. This means three meals -- with the two smaller meals not equalling in size the main meal of the day -- and no snacking, but meat can be eaten at the principle meal.

On those days of fasting and abstinence, fish and meatless soup are traditional (see recipes), as are egg dishes -- pepper and egg sandwiches for Italian Americans. Sundays, of course, are always free of fasting and abstinence; even in the heart of Lent, Sundays are about the glorious Resurrection. This pattern of fasting and abstinence ends after the Vigil Mass of Holy Saturday.

As to special Lenten foods, vegetables, seafoods, salads, pastas, and beans mark the Season, in addition to the meatless soups. The fasting of this time once even precluded the eating of eggs and fats, so the chewy pretzel became the bread and symbol of the times. They'd always been a Christian food, ever since Roman times, their very shape being the creation of monks. The three holes represent the Holy Trinity, and the twists of the dough represent the arms of someone praying. In fact, the word "pretzel" is a German word deriving ultimately from the Latin "bracellae," meaning "little arms" (the Vatican has the oldest known representation of a pretzel, found on a 5th c. manuscript). Below is a recipe for the large, soft, chewy pretzels that go so well with beer:

Soft Pretzels (makes 12)

1 (.25 ounces) package active dry yeast

2 Tablespoons brown sugar

1 1/8 teaspoons salt

1 1/2 cups warm water (110 degrees F)

3 cups all-purpose flour

1 cup bread flour

2 cups warm water (110 degrees F)

1 Tablespoons baking soda dissolved in 6 qt. water in large pot

egg + water for eggwash

2 Tablespoons butter, melted

2 Tablespoons coarse pretzel salt or kosher salt

In a large mixing bowl, dissolve the yeast, brown sugar and salt in 1 1/2 cups warm water. Stir in flour, and knead dough on a floured surface until smooth and elastic, about 8 minutes. Place in a greased bowl, and turn to coat the surface. Cover, and let rise for one hour.

Meanwhile, place parchment on cookie sheets and oil paper.

After dough has risen, cut into 12 pieces. Roll each piece into a 2 to 3 foot, finger-thick rope. With the rope, make a U, cross the ends, twist, and attach to the center of the bottom of the U. Place on the parchment-lined sheets and let rise, uncovered, 15 to 20 minutes. While they are rising, bring the baking soda + water in the pot to a boil. When the pretzels are risen, boil the pretzels in the water for about 3 minutes, turning once, til puffed a bit. Place on sheets and brush with eggwash.

Bake at 450 degrees F for 8 to 10 minutes, or until golden brown. Brush with melted butter, and sprinkle with coarse salt (can use garlic salt or cinnamon sugar instead).

Hot Cross Buns are eaten at breakfast on Good Friday, and there are other special foods eaten on certain days, but you can read about these on the pages dedicated to those dates.

Note: Lent is a good time to start considering any plans you might have for a Mary Garden. Depending on where you live, planting time is approaching! The days of Lenten Embertide are most apt for planning such an endeavor.

Reading

"The Mystery of Lent"

from Dom Gueranger's "The Liturgical Year"

We may be sure that a season so sacred as this of Lent is rich in mysteries. The Church has made it a time of recollection and penance, in preparation for the greatest of all her feasts; she would, therefore, bring into it everything that could excite the faith of her children, and encourage them to go through the arduous work of atonement for their sins. During Septuagesima, we had the number "seventy", which reminds us of those seventy years of captivity in Babylon, after which God's chosen people, being purified from idolatry, was to return to Jerusalem and celebrate the Pasch. It is the number "forty" that the Church now brings before us: a number, as St. Jerome observes, which denotes punishment and affliction.

Let us remember the forty days and forty nights of the deluge sent by God in His anger, when He repented that He had made man, and destroyed the whole human race with the exception of one family. Let us consider how the Hebrew people, in punishment for their ingratitude, wandered forty years in the desert, before they were permitted to enter the promised land. Let us listen to our God commanding the Prophet Ezechiel to lie forty days on his right side, as a figure of the siege which was to bring destruction on Jerusalem.

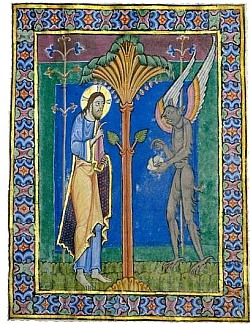

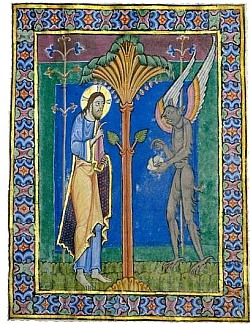

There are two persons in the old Testament who represent the two manifestations of God: Moses, who typifies the Law; and Elias, who is the figure of the Prophets. Both of these are permitted to approach God: the first on Sinai, the second on Horeb; but both of them have to prepare for the great favour by an expiatory fast of forty days.

With these mysterious facts before us, we can understand why it is that the Son of God, having become Man for our salvation and wishing to subject Himself to the pain of fasting, chose the number of forty days. The institution of Lent is thus brought before us with everything that can impress the mind with its solemn character, and with its power of appeasing God and purifying our souls. Let us, therefore, look beyond the little world which surrounds us, and see how the whole Christian universe is, at this very time, offering this forty days' penance as a sacrifice of propitiation to the offended Majesty of God; and let us hope that, as in the case of the Ninivites, He will mercifully accept this year's offering of our atonement, and pardon us our sins.

The number of our days of Lent is, then, a holy mystery: let us now learn, from the liturgy, in what light the Church views her children during these forty days. She considers them as an immense army, fighting day and night against their spiritual enemies. We remember how, on Ash Wednesday, she calls Lent a Christian warfare. In order that we may have that newness of life, which will make us worthy to sing once more our "Alleluia", we must conquer our three enemies: the devil, the flesh, and the world. We are fellow combatants with our Jesus, for He, too, submits to the triple temptation, suggested to Him by satan in person. Therefore, we must have on our armour, and watch unceasingly. And whereas it is of the utmost importance that our hearts be spirited and brave, the Church gives us a war-song of heaven's own making, which can fire even cowards with hope of victory and confidence in God's help: it is the ninetieth Psalm. She inserts the whole of it in the Mass of the first Sunday of Lent, and every day introduces several of its verses into the ferial Office.

She there tells us to rely on the protection, wherewith our heavenly Father covers us, as with a shield; to hope under the shelter of His wings; to have confidence in Him; for that He will deliver us from the snare of the hunter, who had robbed us of the holy liberty of the children of God; to rely upon the succour of the holy angels, who are our brothers, to whom our Lord hath given charge that they keep us in all our ways, and who, when Jesus permitted satan to tempt Him, were the adoring witnesses of His combat, and approached Him, after His victory, proffering to Him their service and homage. Let us well absorb these sentiments wherewith the Church would have us to be inspired; and, during our six weeks' campaign, let us often repeat this admirable canticle, which so fully describes what the soldiers of Christ should be and feel in this season of the great spiritual warfare.

But the Church is not satisfied with thus animating us to the contest with our enemies: she would also have our minds engrossed with thoughts of deepest import; and for this end she puts before us three great subjects, which she will gradually enfold to us between this and the great Easter solemnity. Let us be all attention to these soul-stirring and instructive lessons.

And firstly, there is the conspiracy of the Jews against our Redeemer. It will be brought before us in its whole history, from its first formation to its final consummation on the great Friday, when we shall behold the Son of God hanging on the wood of the cross. The infamous workings of the Synagogue will be brought before us so regularly, that we shall be able to follow the plot in all its details. We shall be inflamed with love for the august Victim, whose meekness, wisdom, and dignity bespeak a God. The divine drama, which began in the cave of Bethlehem, is to close on Calvary, we may assist at it, by meditating on the passages of the Gospel read to us by the Church during these days of Lent.

The second of the subjects offered to us, for our instruction, requires that we should remember how the feast of Easter is to be the day of new birth for our catechumens, and how, in the early ages of the Church, Lent was the immediate and solemn preparation given to the candidates for Baptism. The holy liturgy of the present season retains much of the instruction she used to give to the catechumens; and as we listen to her magnificent lessons from both the old and the new Testament, whereby she completed their "initiation", we ought to think with gratitude of how we were not required to wait years before being made children of God, but were mercifully admitted to Baptism even in our infancy. We shall be led to pray for those new catechumens, who this very year, in far distant countries, are receiving instructions from their zealous missioners, and are looking forward, as did the postulants of the primitive Church, to that grand feast of our Saviour's victory over death, when they are to be cleansed in the waters of Baptism and receive from the contact a new being-regeneration.

Thirdly, we must remember how, formerly, the public penitents, who had been separated on Ash Wednesday from the assembly of the faithful, were the object of the Church's maternal solicitude during the whole forty days of Lent, and were to be admitted to reconciliation on Maundy Thursday, if their repentance were such as to merit this public forgiveness. We shall have the admirable course of instructions, which were originally designed for these penitents, and which the liturgy, faithful as it ever is to such traditions, still retains for our sake. As we read these sublime passages of the Scripture, we shall naturally think upon our own sins, and on what easy terms they were pardoned us; whereas, had we lived in other times, we should have probably been put through the ordeal of a public and severe penance. This will excite us to fervour, for we shall remember that, whatever changes the indulgence of the Church may lead her to make in her discipline, the justice of our God is ever the same. We shall find in all this an additional motive for offering to His divine Majesty the sacrifice of a contrite heart and we shall go through our penances with that cheerful eagerness, which the conviction of our deserving much severer ones always brings with it.

In order to keep up the character of mournfulness and austerity which is so well suited to Lent, the Church, for many centuries, admitted very few feasts into this portion of her year, inasmuch as there is always joy where there is even a spiritual feast. In the fourth century, we have the Council of Laodicea forbidding, in its fifty-first canon, the keeping of a feast or commemoration of any saint during Lent, excepting on the Saturdays or Sundays. The Greek Church rigidly maintained this point of lenten discipline; nor was it till many centuries after the Council of Laodicea that she made an exception for March 25, on which day she now keeps the feast of our Lady's Annunciation.

The Church of Rome maintained this same discipline, at least in principle; but she admitted the feast of the Annunciation at a very early period, and somewhat later, the feast of the apostle St. Mathias, on February 24. During the last few centuries, she has admitted several other feasts into that portion of her general calendar which coincides with Lent; still, she observes a certain restriction, out of respect for the ancient practice.

The reason why the Church of Rome is less severe on this point of excluding the saints' feasts during Lent, is that the Christians of the west have never looked upon the celebration of a feast as incompatible with fasting; the Greeks, on the contrary, believe that the two are irreconcilable, and as a consequence of this principle, never observe Saturday as a fasting-day, because they always keep it as a solemnity, though they make Holy Saturday an exception, and fast upon it. For the same reason, they do not fast upon the Annunciation.

This strange idea gave rise, in or about the seventh century, to a custom which is peculiar to the Greek Church. It is called the "Mass of the Presanctified", that is to say, consecrated in a previous Sacrifice. On each Sunday of Lent, the priest consecrates six Hosts, one of which he receives in that Mass; but the remaining five are reserved for a simple Communion, which is made on each of the five following days, without the holy Sacrifice being offered. The Latin Church practices this rite only once in the year, that is, on Good Friday, and this in commemoration of a sublime mystery, which we will explain in its proper place.

This custom of the Greek Church was evidently suggested by the forty-ninth canon of the Council of Laodicea, which forbids the offering of bread for the Sacrifice during Lent, excepting on the Saturdays and Sundays. The Greeks, some centuries later on, concluded from this canon that the celebration of the holy Sacrifice was incompatible with fasting; and we learn from the controversy they had, in the ninth century, with the legate Humbert, that the "Mass of the Presanctified" (which has no other authority to rest on save a canon of the famous Council in "Trullo", held in 692) was justified by the Greeks on this absurd plea, that the Communion of the Body and Blood of our Lord broke the lenten fast.

The Greeks celebrate this rite in the evening, after Vespers, and the priest alone communicates, as is done now in the Roman liturgy on Good Friday. But for many centuries they have made an exception for the Annunciation; they interrupt the lenten fast on this feast, they celebrate Mass, and the faithful are allowed to receive holy Communion.

The canon of the Council of Laodicea was probably never received in the western Church. If the suspension of the holy Sacrifice during Lent was ever practiced in Rome, it was only on the Thursdays; and even that custom was abandoned in the eighth century, as we learn from Anastasius the Librarian, who tells us that Pope St. Gregory II., desiring to complete the Roman sacramentary, added Masses for the Thursdays of the first five weeks of Lent. It is difficult to assign the reason of this interruption of the Mass on Thursdays in the Roman Church, or of the like custom observed by the Church of Milan on the Fridays of Lent. The explanations we have found in different authors are not satisfactory. As far as Milan is concerned, we are inclined to think that, not satisfied with the mere adoption of the Roman usage of not celebrating Mass on Good Friday, the Ambrosian Church extended the rite to all the Fridays of Lent.

After thus briefly alluding to these details, we must close our present chapter by a few words on the holy rites which are now observed, during Lent, in our western Churches. We have explained several of these in our 'Septuagesima.' The suspension of the "Alleluia"; the purple vestments; the laying aside of the deacon's dalmatic, and the subdeacon's tunic; the omission of the two joyful canticles "Gloria in excelsis" and "Te Deum"; the substitution of the mournful "Tract" for the Alleluia-verse in the Mass; the "Benedicamus Domino" instead of the "Ite Missa est"; the additional prayer said over the people after the Postcommunions on ferial days; the celebration of the Vesper Office before midday, excepting on the Sundays: all these are familiar to our readers. We have now only to mention, in addition, the genuflections prescribed for the conclusion of all the Hours of the Divine Office on ferias, and the rubric which bids the choir to kneel, on those same days, during the Canon of the Mass.

There were other ceremonies peculiar to the season of Lent, which were observed in the Churches of the west, but which have now, for many centuries, fallen into general disuse; we say general, because they are still partially kept up in some places. Of these rites, the most imposing was that of putting up a large veil between the choir and the altar, so that neither clergy nor people could look upon the holy mysteries celebrated within the sanctuary. This veil-which was called "the Curtain", and, generally speaking, was of a purple colour-was a symbol of the penance to which the sinner ought to subject himself, in order to merit the sight of that divine Majesty, before whose face he had committed so many outrages. It signified, moreover, the humiliations endured by our Redeemer, who was a stumbling-block to the proud Synagogue. But as a veil that is suddenly drawn aside, these humiliations were to give way, and be changed into the glories of the Resurrection. Among other places where this rite is still observed, we may mention the metropolitan church of Paris, "Notre Dame."

It was the custom also, in many churches, to veil the crucifix and the statues of the saints as soon as Lent began; in order to excite the faithful to a livelier sense of penance, they were deprived of the consolation which the sight of these holy images always brings to the soul. But this custom, which is still retained in some places, was less general than the more expressive one used in the Roman Church, which we will explain in our next volume-the veiling of the crucifix and statues only in Passiontide.

We learn from the ceremonials of the middle ages that, during Lent, and particularly on the Wednesdays and Fridays, processions used frequently to be made from one church to another. In monasteries, these processions were made in the cloister, and barefooted. This custom was suggested by the practice of Rome, where there is a "Station" for every day of Lent which, for many centuries, began by a procession to the stational church.

Lastly, the Church has always been in the habit of adding to her prayers during the season of Lent. Her discipline was, until recently, that, on ferias, in cathedral and collegiate churches which were not exempted by a custom to the contrary, the following additions were made to the canonical Hours: on Monday, the Office of the Dead; on Wednesday, the Gradual Psalms; and on Friday, the Penitential Psalms. In some churches, during the middle ages, the whole Psalter was added each week of Lent to the usual Office.

|